Your Name in Print

On being a published historian

It’s a lovely feeling. That thwack as a neatly wrapped, brand-new magazine lands on your doormat. It’s even better when your own work is inside. This month I had an article published in The Historians Magazine, and you can get yourself a copy of it here. This is not the first time my writing has been in print but is the first time it has been published explicitly as the work of an historian, which does feel different.

The Historians is a relatively new publication, founded on the excellent and inclusive premise that anyone can be an historian. There is an application and editorial process in order to be published, but crucially, anyone can submit to The Historians no matter what stage they are at in their historical career. It doesn’t matter if you’re an autodidact or unaffiliated with any academic institution, and I adore this complete lack of gatekeeping. As I have mentioned before, the British publishing industry typically won’t go anywhere near a history book proposal unless the author is a journalist, employed at a university or a television/social media celebrity, which is to the detriment of readers. Cultural gatekeeping is pernicious because it prevents the excavation of differing stories and attitudes, thereby limiting our capacity for empathy and understanding. Hence my delight at the introduction of The Historians, which I hope will be a starting step for many early-career scholars.

The article of mine they published is about a completely different century and continent from my usual research. This was intentional. I like to set myself the challenge of researching a topic I know nothing about, and then writing an explanation that is as succinct as possible. I find this a useful test of historical skills, and stepping outside your usual territory, being open to whatever you might find, keeps you fresh. Following your curiosity is a good way to keep the academic sensibility alive, and in this instance I found I had a lot of questions about Canadian history.

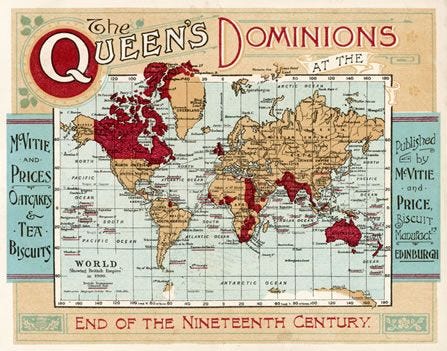

The history and culture of Canada is not well-known in England. I cannot recall a single mention of Canada during my time at school, or in any of my three degrees, and I realised there were so many things about Canada that confused me. How and why is Canada both Anglo and French? Why didn’t Canada become independent when the USA did? How did the distant, enormous Canadian territories first become part of the British Empire, and why is Canada still in the Commonwealth today? And perhaps most puzzling of all, why are on earth are British Royals still on Canada’s money? To answer these questions, I had to go back to the Canadian Revolution of 1837-38.

Firstly, I call this movement a revolution, but if you look it up anywhere these events will almost always be called a rebellion. The importance of the nuances around this difference are a topic for another day, but I will recommend a book that places the Canadian Revolution/Rebellion in a nineteenth century revolutionary context - The Idea of Liberty in Canada during the Age of Atlantic Revolutions, 1776–1838 by Michel Ducharme.

While nineteenth century Canada is not my normal line of research, British imperial history is. I’m endlessly fascinated by the many self-interested ways in which Britain has acted on the world stage, and how little we discuss this activity today. If it didn’t occur on this small Atlantic island, it’s like it never happened. I’m currently reading The Fatal Shore, Robert Hughes’ landmark history of Britain’s convict colonisation of Australia, and I’m finding it utterly mind-blowing. The story Hughes tells is undeniably one of British history, driven and shaped by British actors and contextualises the extraordinary decision to create a gulag on the other side of the world, in a land that had only once before been visited by white men. Despite being driven entirely by domestic British interests, this is not a narrative that I have ever seen included in any histories of the Georgian and Victorian eras. Suffice to say, the only mention of Australia throughout my education was the doomed endeavour at Gallipoli. This is why increasing access to history publications matters. Greater diversity of historical authors will provide both a wider range of perspectives and historical topics.

Anyone who tries to argue that Britain’s imperial history is irrelevant to Britain’s domestic history is plain wrong. To appreciate this truth, one need only look at the now long-forgotten imperial figures who were equally active at home and abroad. For example, consider John Lambton, the first Earl of Durham (1792 –1840) who was not only an influential Whig parliamentarian with a Prime Minister for a father-in-law, but also part of the first attempt to colonise New Zealand and served as Britain’s Ambassador to Russia. Lambton had two of the most hilariously contradictory nicknames I’ve ever come across. The first was ‘Radical Jack’, because he helped draft the Great Reform Act of 1832 and supported liberalising restrictions on English Catholicism. The second was ‘Jog Along Jack’. When he was asked what he considered an adequate income for an Englishman, Lambton replied ‘a man might jog along comfortably enough on £40,000 a year’. For context, the 2025 equivalent would be an annual take-home salary of almost £4 million… Man of the people right there. As telling as this is, Lambton should be best known for his role as Governor General and High Commissioner of British North America, when he authored the Durham Report, which became the bedrock of British imperialism in the nineteenth and twentieth century. The sorts of history books that get published today tend not to feature men such as Lambton, but they should. Not to glorify them, but to help us comprehend the past and present. Lambton’s life is still relevant today, living as he did in a time when the very rich blithely determined the fates of millions around the world.

The prose of my article in The Historians has been chopped about a little, but I nonetheless think it provides a decent overview of a complex moment of imperial history. There’s something in this topic for everyone, political agitation, religious conflict, military action, romantics, reactionaries, winners and losers. Ultimately though the Canadian Revolution of 1837-38 is an example of how ruthlessly successful the British imperial project was. If you want to learn more about this thwarted attempt to gain liberty, you can read about it here.